|

CHAPTER TITLES

|

Chapter 2 WHY DOES MUSIC MAKE SEX BETTER ? The inner experience of territory "... it appears probable that the progenitors of man, either the males or females or both sexes, before acquiring the power of expressing their mutual love in articulate language, endeavoured to charm each other with musical notes and rhythm." [65]

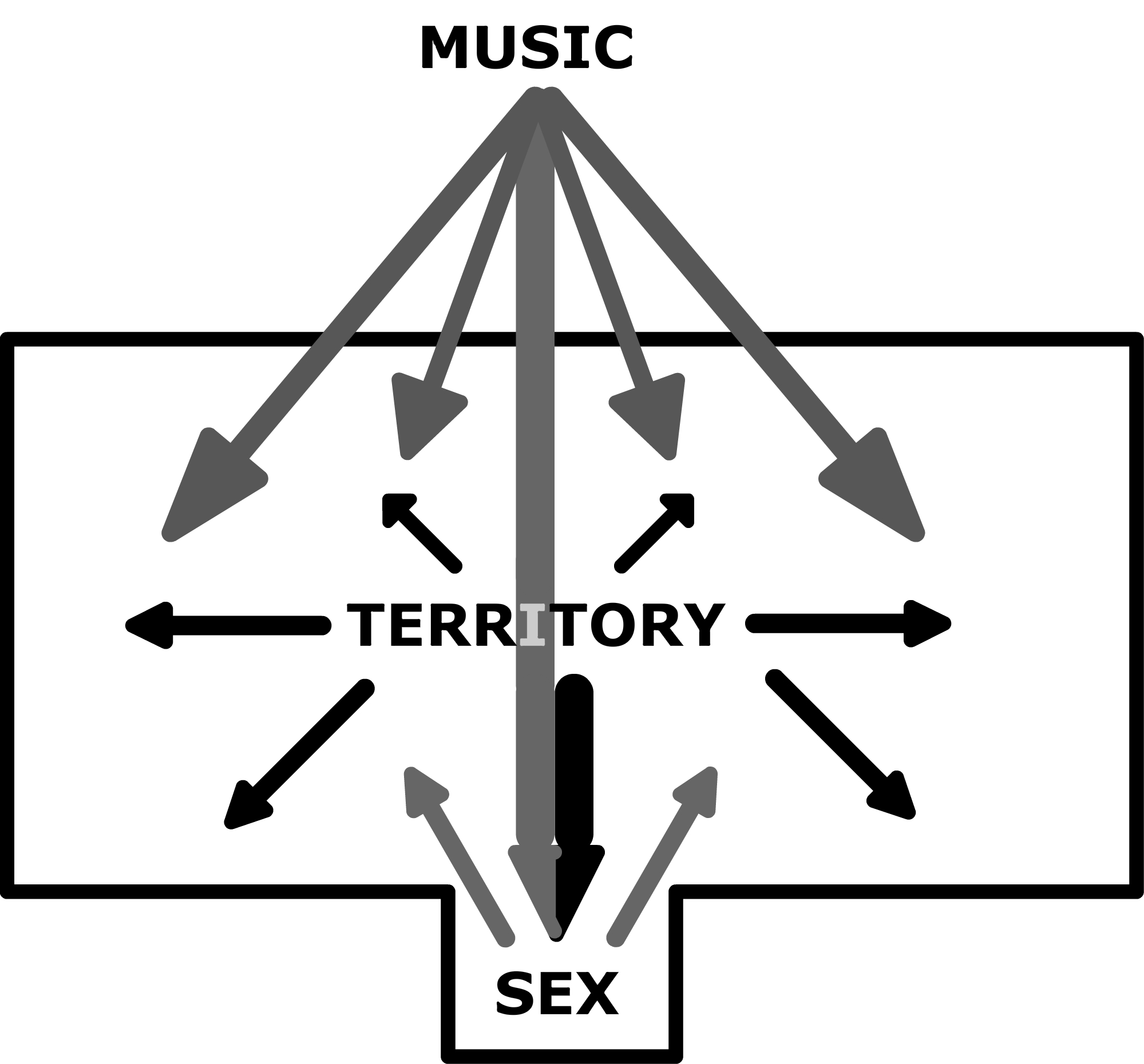

Sex and bedrooms. They go together. If your home is your territory, your bedroom is its protected core, and your bed is its innermost sanctum. The bed is where you nest, and it is the safest place you know — a place where you finally end your vigilance and let yourself fall asleep. The bed signifies territory. As long as sex remains an act of intense vulnerability, of being oblivious to much of one’s surroundings, most sex will take place in a bed. This link between territory and sex can be reinforced by music, which is why people play music while in bed having sex. The entire argument of this chapter can be summarized as follows: This complex relationship between sex, territory, and music is exemplified by behavior of the New York heavy metal band Manowar. In 1984 Manowar entered the Guinness Book of World Records for the loudest performance on record. Loudness is physically a way to conquer territory, as shown by the Long Range Acoustic Devices of the US military. [66] For Manowar, controlling the space with sound is directly connected to a territorial metaphor; they profess themselves to be The Kings of Metal. Their 8th album, released in 1996, is called Louder Than Hell, and in the words of their bassist Joey DeMaio, "We have a saying that a speaker sounds best just before it blows." [67] According to Manowar there is a direct connection between loudness and sex. DeMaio explained in a German interview, "The reason for [playing so loud] is the vibration is good for the girls. It goes up their legs and hits the spot… [whistles] Orgasm!" [68] While it seems unlikely that scientists will ever verify this claim, for a metal band, Manowar have more than their fair share of female fans. Occasionally a few of their sexiest groupies will mount the stage to disrobe for the musicians and then offer their bodies for brief sexual acts on stage, all while the guitars continue to crash out their ear-splitting mating call.[69] This is marvelous for the musicians, but not so obviously appealing for the fans. Manowar, which has a self-proclaimed reputation for being outside of mainstream commercial heavy metal, has many fans across the globe. Their supporters are known by the theatrical moniker The Army of the Immortals, and they are ostentatiously loyal, in many cases signing their fan mail in blood. Even though there seems to be a higher percentage of women at Manowar gigs than at many other metal shows, as with all heavy metal, the women are vastly outnumbered by men. If sex and territory go together, most men at a Manowar concert must realize that, statistically speaking, they are fighting a losing battle, and very few of them will obtain a woman at the concert. Why do they still come? Because territory is intrinsically valuable. If territory were only used for sex, then people would never bother with it on their own. In fact people perform territorial acts often when by themselves. This frequently is why people play music for themselves. Any time you put some music on in order to hear it but not specifically listen to it, such that it is background or ambience, that may be motivated by a need for territory — much like painting the walls of your room a color you find comfortable. The Manowar example shows that people get sexually attracted when you combine music and territory: deliberately territorial music (e.g., loud and dominant) when mixed with displays of social territory (e.g., a big audience) is especially potent as a sexual catalyst (see Figure 2.1). However, the fans show that not all music is aimed at sex, and not all territory leads to (or is geared toward) sex; just as music is valued unto itself, territory has intrinsic value — it is an emotional experience that strengthens you.

Figure 2.1. How territorial music supercharges the ability of social territory to lead to sex. Although territory can lead to sex (thick black downward arrow), it can lead to many other territorial experiences (i.e., emotions related to territory such as confidence or soothing, other black arrows). Sex is "one corner" of the territorial experience, but not all sex has to begin on your own territory because sex itself is a way to gather more territory (diagonally upward gray arrows). Music leads to many territorial experiences (if it is music "of your territory", set of diagonally downward gray arrows), but music that specifically stresses that it is your territory (loud, showing off, singing "I am the best", gray arrow straight down) leads to the center of territory, and combined with displays of social territory, such as having a big audience, will make the musician very desirable (combined black and grey downward arrow). Not only is there value to territory that is independent of competing for sex, but in some cases animals act as though territory is more important than sex. A vivid example of this is the Uganda kob (Adenota kob thomasi), an antelope-like animal where the males compete directly for territory but not for females. All mating takes place within a male’s territory, a court, which is the size and shape of a putting green of short grass, surrounded by another forty such territories (a lek), with the most active and attractive territories being at the center of the lek.[70] Each court is gladiatorially guarded by one pugnacious male, and the territories are hotly contested. They are crucial for a male's reproductive success, as there are only 13 known territorial breeding grounds for a population of 10,000 kob in their habitat of 100 square miles; that works out to about 520 territories for 5000 males, so on any given day only 1 in 10 males will have a territory. The holder of each court is challenged by other kobs, sometimes with aggressive displays but usually with violence. If a male wins a fight, the ground is his. But when he leaves to graze or drink, which happens twice per day, he loses his ground. Meanwhile, females are drawn on to the lek but are heedless of the powerful buck, as if the grass never tasted so sweet as on this lek. While on one such territory the female may mate with the male, but if the female walks over the boundary between one territory and the next, the first male makes no protest and loses interest as the next male becomes the new host for that female. What makes lekking behavior so interesting is that the animals are doing all their fighting and mate selection based on territory — sex almost seems an afterthought. [71] For example, a group of female kob may be accompanied by a male while foraging, which is convenient and supportive, but does the male no good reproductively. The females will not mate with this companion. No territory, no nookie. To put status and territory into perspective, 500 years ago most European human males would not have had sex before the age of 25 except if they could afford a prostitute; save for the privileged, celibacy was high, servitude was common, and marriage came late if at all.[72] The modern European right to start a family and the idea that everyone should be able to have a boyfriend or girlfriend if they want one is not how things have always been.[73] Being alpha is a big deal, both for humans and for animals. What does the male kob think about all of this? "Full speed ahead." To gain territory he charges fervently into battle, even though his chances are slim because the current territory holder nearly always wins. And every time a male returns to his territory after foraging (or after a lion, automobile or elephant makes all the kob abandon the lek), he has to fight his way back onto his territory. While some males only last a day, there have been observations of males holding court as long as seventy-five days. All that fighting seems a lot of work for a patch of grass no bigger than a tennis court. You might be thinking, "Location, location, location," but you would be wrong. Territory is not a place — it is a state of mind. Whether you are talking about a gang on their turf, a priest in his chapel, or a Jane Austen heroine in her family home, there is a psychical aspect that they all share. As a thought experiment, consider how you feel in different places. Are there certain places that make you feel assured, while others make you anxious? In a dark city alley, do you ever find yourself thinking, "I don’t belong here"? It is more than the lighting, because in the center of your own territory (in your bed) you can sleep unarmed and naked in the dark, while a dark and lonely alley is not fixed by street lamps. Think of how the outcome of a heated argument depends upon who has the home turf advantage, and why international negotiations to end wars usually take place literally in a neutral territory. The home is not simply a space to be contained in. It is a "center" not in a geometrical sense, but in a psychological one. The home empowers us: we tend to view it as a source of our strength. Although psychological, this empowerment takes on a physical aspect into the material world. While all sportsmen know of the home team advantage, few are aware of how carefully it has been scientifically validated. Scientists, making mathematical analyses, have consistently found that teams playing on their own turf have a small but statistically reliable increased probability of winning. [74] It is not true for all teams (a minority of teams have better luck when playing away). It is not meaningful for any single game (or even for a small series of games). But over the course of a season, it can be measured in virtually every team sport tested, whether professional or amateur. [75] Scientists have repeatedly tried to ascribe the home advantage to an objective basis, such as familiarity with the field, travel fatigue, or the importance of the game; however, when each of these explanations is carefully tested, they are found to have little or no effect. [76] For English soccer, the team with the home advantage racks up approximately 1/2 of an extra goal per game, and it does not matter what level or league of play. The home advantage becomes less once a team enters a new league, and then it becomes greater over time as they settle in to the new league; this invalidates the theory that the visiting team underperforms because they are unfamiliar with the playing field or stadium. The mysterious source of the home advantage seems to have psychological origins. For example, when competing at home, rugby players who took a psychological test one hour before playing scored higher on Vigor and Self-confidence, and lower on Tension, Depression, Anger, Fatigue, Confusion, Cognitive Anxiety, and Somatic Anxiety.[77] The crowds' effects on the home team are not the root of this advantage. In fact, the players’ reaction to cheering is not necessarily positive, as was demonstrated by a unique scientific opportunity. When a measles epidemic precipitated a quarantine that excluded fans from eleven basketball games, the performance of the two affected teams improved; in terms of points scored and percentages of successful attempts, both teams performed better in the absence of spectators.[78] So the home advantage is not due to any obvious physical factor such as familiarity with the playing field or cheering. The mystery of the home advantage seems obvious in animals: territory. When two competitors of comparable size and ability fight, the one on its own territory usually wins. In humans I will call this phenomenon social territory, because not all social territory in humans is tied specifically to a piece of land. This feature of social territory in which the territorial experience transcends the boundaries of space and place was highlighted in 2000 by the international union of Roma, better known as the gypsies. It is not surprising that the gypsies are famed for their music; they need music to reinforce their social territory. Emil Scuka, the founder of the first Roma party of Czechoslovakia, stated,

In humans we seem to prefer the term identity, and a sociologist might categorize much of these effects as part of social identity. [80] The problem with social identity is that sociologists have not developed methods for measuring "identity" in a rabbit or a hummingbird. In humans music very often reinforces this psychological phenomenon whether you call it identity or territory. Only one other primate besides man has a complicated singing behavior: the gibbon.[81] A mated pair of gibbons will often sing "duets" together in the morning, and the song is plainly to reinforce territory. [82] This book sticks with the term social territory because the term social identity cannot be easily applied to animals' mental states; the phenomenon of social territory is seen in both animals and man, and is most clearly demonstrated by the fact that males with demonstrable territory are sexually attractive, while the same males without territory are not. Paris, September 1827: Hector Berlioz (1803-1869), an impecunious music student at the conservatoire, first lays eyes on the celebrated Irish actress Harriet Smithson (1800-1854). After he watches her play Ophelia in Hamlet at the ThÉâtre de l'Odéon, he falls violently in love with her, and confronting her backstage, he loudly proclaims his love for her.[83] She is scared senseless, but her initial rejection does little to cool his ardor. In addition to barraging her with so many letters that she eventually instructs her maid not to accept them, in the summer of 1828 Berlioz organizes a concert of his own music to win her love. This attempt at sexual display fails singularly, as Smithson is not informed of the concert. Haunted by his obsession for Smithson, for the next year and a half Berlioz composes his most famous work, Symphonie Fantastique, which tells his romanticized story of the dreams and suffering of an artist pursuing his beloved. Fantasizing about restoring his status in the wake of his rejected love, the denouement arrives after the artist thought he had killed her, with the reappearance of his beloved in the midst of a witches' Sabbath. This sort of music-making is not the most direct strategy for seducing a woman. The most attractive (and territorial) music would focus on the man being strong in the material world, rather than being weak, day dreaming, and wishing he could kill the indomitable girl. However, even Berlioz’s unusual musical narratives can work their charms, albeit in unexpected ways, if they lead to demonstrable territory. In 1830 Berlioz finally achieves his musical ambition of winning the Prix de Rome, essentially a scholarship connected to a 5 year pension and travel for study in Rome, which has eluded him for the previous five years. He now has status and territory. At about the time of his newfound recognition and financial security, he becomes the prey of a new woman, Camille Moke, an irrepressible and wanton pianist. She notices the virginal Berlioz and asks one of his friends about him,[84] but is told in no uncertain terms that Berlioz is totally obsessed with Smithson and that Moke has no hope. This only strengthens her resolve to make Berlioz fall madly in love with her. She succeeds in less than six months; she and Berlioz are engaged by the end of that year. Unfortunately for Berlioz, the terms of the Prix de Rome require him to study in Rome — without Moke. After three months in Rome, Berlioz has not received any correspondence from Moke, so he impulsively sets off for Paris to get some news. An unsympathetic letter from Moke's mother finds him while he is still traveling across Italy, and the news is bad. In Berlioz's short absence, Moke has decided to break off their relationship and to marry the scion of the wealthy piano manufacturer, Ignace Pleyel. [85] In a nutshell, as soon as Berlioz abandons his territory in Paris, Moke allies herself with another man in Paris who is rich and has even greater territory than that demonstrated by Berlioz's inchoate fame. This is not only a loss of face, but a loss of territory — he has lost his fiancée (his one sexual conquest) to another man, and this enflames Berlioz’s rage and aggression. True to his Romantic spirit, Berlioz concocts a melodramatic scheme to exact a bloody revenge — a triple murder and suicide. Berlioz's stratagem is to gain entrance to their home disguised as a cleaning girl, and then reveal himself before gunning down Pleyel, his ex-fiancée, and her detested mother.[86] He goes so far as to buy a specially altered maid's dress and a hat with a thick green veil. For the killing, he has brought two pistols, and poison (with which to kill himself should the pistols fail). This is how he imagines what would happen when he gets to Paris:

His reason returns just before he loses his prize money; he is threatened with having to forfeit the Prix de Rome (the real territory he has won) if he does not stop before crossing the French border. Back in Rome, Berlioz sublimates his fury into his musical work, culminating in composing the overture to King Lear, the story of trusting man victimized by evil women — another of Berlioz's plots that parallels his own life. Two and one half years after winning the Prix de Rome and living abroad, Berlioz returns to Paris where he produces a concert of Symphony Fantastique; this time he arranges for friends to introduce him properly to Smithson. Smithson has no idea the music has been composed for her when her friends take her to the concert on 9 December 1832. She realizes something might be afoot when during Lélio, the sequel to Symphony Fantastique, an actor proclaims, 'Oh, if I could only find her, the Juliet, the Ophelia that my heart cries out for!' Smithson has just been through a spell of bad luck professionally, and is now wistful about Berlioz's love for her. What happens next is best described by Berlioz himself: " 'God!' she thought: 'Juliet — Ophelia! Am I dreaming? I can no longer doubt. It is of me he speaks. He loves me still.' From that moment, so she has often told me, she felt the room reel about her; she heard no more but sat in a dream, and at the end returned home like a sleepwalker, hardly aware of what was happening." [88] Given her poor treatment of Berlioz, it is incomprehensible to her — not that she is the Muse of this genius, but that he is still in love with her. With his music gaining a following, it firmly establishes Berlioz's territory, so he is attractive enough to restart his courtship auspiciously, and he ends up marrying the girl of his dreams, literally.[88] It is not just status and success that wins the girl [90] — it is territory, as Berlioz found to his cost after he left Paris and lost Camille Moke. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * [SNIP] FOOTNOTES[65] Darwin C (1871). The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex, Volume II, Chapter 19, London: John Murray, pp. 337. [66] See Cusick SG (2006). Music as torture / Music as weapon. TRANS Revista transcultural de Música. Number 10. (Barcelona: Sociedad de Etnomusicología). For the manufacturer of LRADs, see www.atcsd.com [67] Harris C and Wiederhorn J (2007). Metal File: Manowar, A Life Once Lost, Origin & More News That Rules. MTV News, 09 Feb. www.mtv.com/news/articles/1552016/20070208/manowar.jhtml [68] The interview in April 2002 was with Stefan Raab on TV Total, a German late night comedy talk show. It was accessed on 28 April 2010 at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fb-hQoGHKpQ [69] A film of a female groupie on stage at an Athens 4 April 2007 Manowar concert was downloaded (19 Jan 2010) at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y9STO5p8Qj0. In another clip http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VhEmYtljTkU&feature=related she is shown having her nipple sucked on stage by a Greek guitarist. In another clip a scantily clad Finnish groupie gets on stage for an extended kiss with the singer http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mxtm8_jgb08&feature=related. A set of clips of women on stage with Manowar is on http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5uQY_GzP2GM [70] This information about the Uganda Kob concerns those in the Semliki Game Reserve near Fort Portal Uganda. Buechner HK (1961). Territorial behavior in Uganda Kob. Science 133: 698-9. [71] The theory of territory is that males fight over territory, not over mates. See Nice MM (1941). The role of territory in bird life. The American midland Naturalist 26(3): 441-487. [72] Hajnal J (1965). European marriage patterns in perspective. In Glass DV & Eversley DEC (eds), Population in History. Chicago: Aldine Publishing. [73] Article 12 of the The European Convention on Human Rights (1948) states "Men and women of marriageable age have the right to marry and to found a family, according to the national laws governing the exercise of this right." This simply means that the state cannot prevent marriage; in the past there have been laws prohibiting marriage based on a variety of issues, including lack of sufficient income. [74] Courneya KS & Carron AV (1992). The Home Advantage in Sport Competitions: A Literature Review. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 14(1): 13-27. [75] Carron AV, Loughhead TM & Bray SR (2005). The home advantage in sport competitions: Courneya and Carron’s (1992) conceptual framework a decade later. Journal of Sports Sciences 23(4): 395 – 407. [76] Clarke SR, Norman JM (1995). Home ground advantage of individual clubs in English soccer. The Statistician 44(4): 509-521. [77] Terry PC, Walrond N, Carron AV (1998). The influence of game location on athletes’ psychological states. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 1(1): 29-37. [78] Moore JC & Brylinsky JA (1993). Spectator effect on team performance in college basketball. Journal of Sport Behavior 16: 77–84. [79] Berezin M (2003). “Territory, emotion and identity: spatial recalibration in a new Europe.” In Berezin M & Schain M (eds.) Europe with Borders: Remapping Territory, Citizenship and Identity in a Transnational Age. London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [80] Tajfel H, Turner J (1979). An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In Austin WG, Worchel S (Eds) The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks-Cole, pp. 94–109. [81] Indris (another primate) have what are sometimes called songs, but these calls are not really as complicated (or as acquired) as human, gibbon or bird song. [82]Geissman T (2000). Gibbon songs and human music from an evolutionary perspective. In Wallin NL, Merker B, Brown S (eds.). The origins of music. (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press) pp. 103-123. [83] From Berlioz H (2002). The Memoirs of Hector Berlioz. Cairns D (editor & translator). London: Everyman’s Library Classics. [84] It is sometimes assumed that Moke was Berlioz’s first lover, although not his first obsession. [85] Her marriage to Pleyel broke down after a few years because of her "disorderly behaviour and persistent infidelity". She went on to become a recognized pianist in her own right. [86] Moke’s mother is an ongoing issue for Berlioz. It is she who most opposed the marriage, and she sent him the letter telling him the engagement is off. Even when the relationship was ongoing, as lovers Berlioz and Moke would uncharitably refer to Moke's mother as l'hippopotame. [87] From Berlioz H (2002). The Memoirs of Hector Berlioz. Cairns D (editor & translator). London: Everyman’s Library Classics. Moke’s mother had always been opposed to the engagement of her daughter to Berlioz because the marriage would not bring her daughter the requisite rank or wealth. [88] From Berlioz H (2002) The Memoirs of Hector Berlioz. Cairns D (editor & translator). London: Everyman’s Library Classics. [89] Thus began the relationship that begot their doomed marriage. With her career dwindling, Harriet Smithson slid into alcoholism, and her behaviour became volatile. After five years of marriage, Berlioz left his wife and 5-year-old son to reside with his mistress, the opera singer Marie Récio. [90] To test whether human music results in reproductive success for males, Geoffrey Miller compared the recorded output of prominent jazz, rock, and classical musicians; he found that males produced ten times as much music as females. Furthermore, the output of the males peaked near the age of maximum mating effort. Thus, according to Miller, music-making in humans acts as a male courtship display to attract females. Miller G (2000). Evolution of human music through sexual selection. In Wallin NL, Merker B & Brown S (Eds), The Origins of Music. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 329–360. An excerpt from You Are What You Hear: How Music and Territory make Us Who We Are, By Harry Witchel, published by Algora Publishing. Copyright 2010 by Harry Witchel. www.youarewhatyouhear.co.uk |